I’m lying down on my back in a tent, staring at the starry sky. The forest is alive: it’s ringing with the perpetual static of crickets, whirring cicadas, snapping branches, and a polyphony of trilling, whistling, and chirping birds. One sound that seems to be particularly persistent is a shrill little shriek, piercing the air incessantly every 30 seconds or so. I wonder who could be making it. It could be a mammal — perhaps a fox? It also sounds a bit like a raccoon, but less spastic. But the noise seems to be coming from above, not far away, making me think that it must be a bird. It is too dark to see anything, so I just keep on wondering.

I lie there, unable to fall asleep, thinking about all the creatures that live in the swamp: from insects and frogs to panthers and alligators. The Everglades are home to 350 species of birds, 300 kinds of fresh and saltwater fish, 50 different reptiles, and 40 types of mammals. It is the last remaining habitat of the Florida panther, with only about 2,000 animals remaining, as well as another 36 threatened species at risk of disappearing. The wilderness itself is shrinking every day: of the original Everglades area, only 50 percent remains today, but only less than half of that area is protected as the Everglades National Park and the rest is slowly but surely being developed for agricultural and urban use.

Before the late 19th century, it was thought to be impenetrable to humans. A labyrinth of sawgrass and mangrove canals, where alligators and American crocodiles lurk, was too dense to be navigable by European ships. But that does not mean that this land — or water, as there seems to be much more water than land — was without people. As far as 15,000 years ago, the Calusa and Tequesta people called this area their home, and later the Seminoles moved in from the north to assimilate with them.

The Seminoles call this place Pahokee, which means "grassy water" — a much more appropriate name than “glades” which carries with it an inability to fathom a landscape that is not characterized by solid land and dry woods. That same inability to conceptualize land not being utilized for productivity, resources, and profit led to the compulsive desire to “drain the swamp” the European colonizers brought with them. Luckily, most of these efforts failed miserably, and after more than a hundred years of trying, the U.S. government finally gave up and gave the Everglades region a protected status.

The ecology of Pahokee is shaped by its unique geography: a combination of low elevation, seasonal tropical climate, and geology. The Florida bedrock is formed from layers of porous limestone that create a very wide, low-slope water-bearing surface. Every summer, when the rainy season fills up Florida’s large rivers that converge at Lake Okeechobee, the lake spills over onto this giant plane and flows south to sea at a snail’s pace of half a mile per day. This massive slow-moving 60-mile-wide river travels for nearly 100 miles before it reaches Florida Bay, taking multiple years to carry the rainwater to the ocean.

The precise boundary between where the terra firma ends and the aquatic realm begins is impossible to establish. The salty seawater and the fresh rainwater push and pull with the undulating forces of floods and tides, competing for mere inches of elevation. This mixing supports the largest mangrove ecosystem in the Western Hemisphere, which recharges the South Florida aquifer. Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach all get their water delivered and filtered by nature, as it passes through the mangrove root systems and the porous limestone over many months.

The water flow dictates the pace of life of every creature in the swamp: the alligators do not like to get disturbed as they float, looking catatonic, in the myriad of natural canals. The birds take their time wading through the swamp, occasionally shooing off one of their kin or spearfishing with their long beaks. The elegant egrets, majestic herons, shy storks, nervous spoonbills, and gregarious cormorants seem to find enough food to coexist peacefully in their wide-open home. Only humans think that there is not enough space and resources for everyone, as they keep encroaching on the other animals’ territory.

Drain the swamp. Put in a highway — then another, faster one. Build a gas station to service the cars, and some businesses to bring in tourism. Straighten the river, funnel it into a reinforced canal, then control its flow through levies and dikes. Add in boardwalks, condos, boat ramps, quarries, and arable fields. Why do we have such a strong drive to change our environment? What about it is “not good enough” for us? What is it with this futile urge to build, pave over everything, and erect ugly square structures in places where organic natural shapes are meant to prevail?

Why not leave it as is, a beautiful River of Grass, taking its time as it trickles down to its final destination?

The night begins to fade. The noises are dying down — even the nocturnal animals need their time to rest. In the void left by their silence, the drip from the moisture-saturated air takes over the soundscape. But the little shrieking noises persist into the dawn. I guess whoever is making them does not need to get up for work. I begin to make my way up, heat up water for tea and make breakfast.

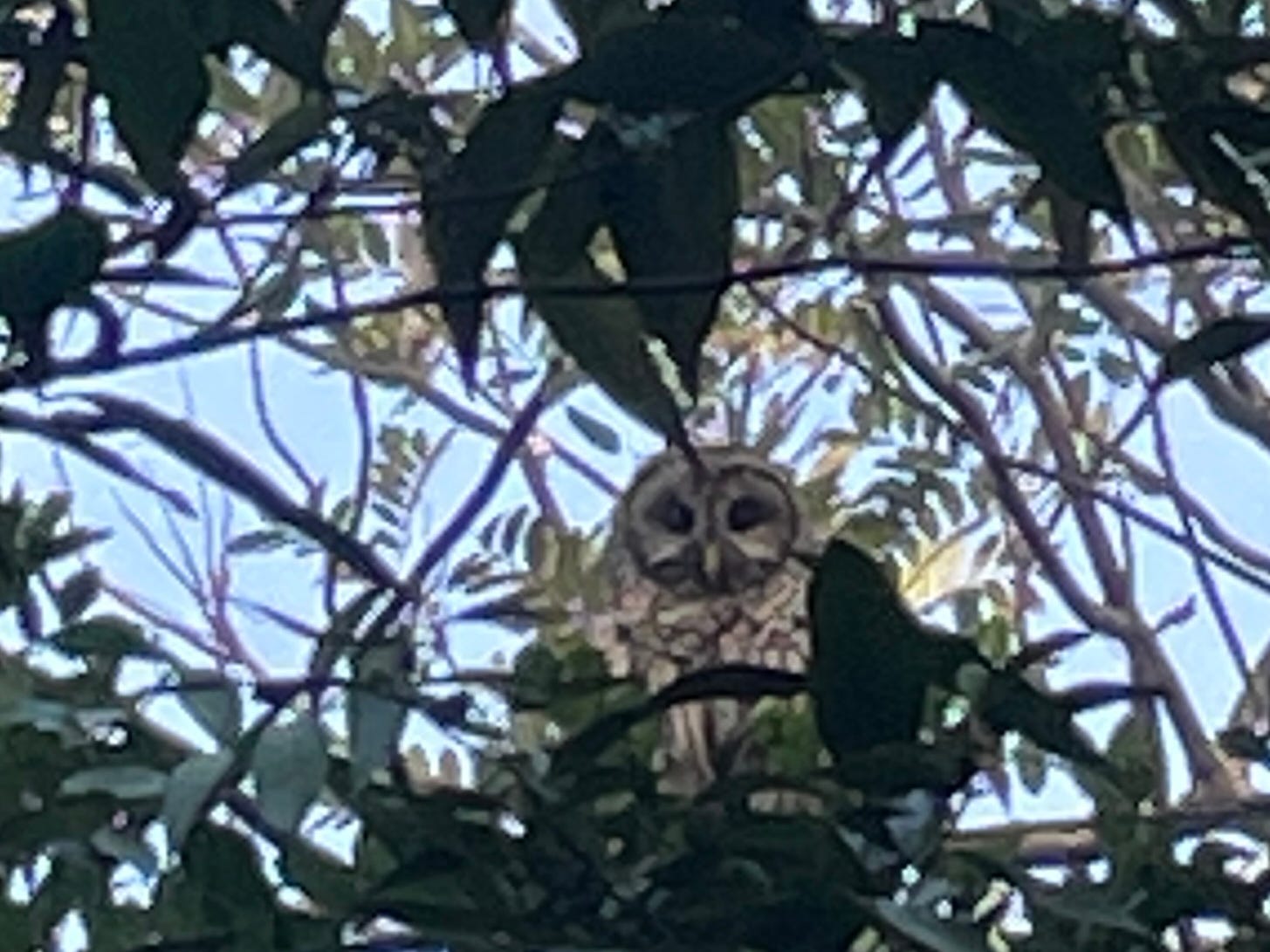

All of a sudden, a big swoop: I see landing on a tall branch right above me a large barred owl. It looks down at me, its round face fascinatingly human-like. We look at each other for a bit, but it wins the staring contest as my neck gets tired from looking up. I continue with my morning routine until another loud screech pierces the air right above me and I glance up to see a baby owl making its way toward the tall branch in short flapping jumps. A second, even smaller one, follows, its little wings outstretched for balance. They take turns shrieking and I finally know what all this fuss is about.

The first baby owl gets to the end of the protruding branch, shaking it so much that it makes me nervous. It takes its breakfast from the mother’s mouth – but it is not satisfied for long, as it resumes its stubborn, ravening cry. Its sibling competes for attention. The mom has no choice but to take off for perhaps one last catch of the night to satisfy her hungry babies.

Luckily, Pahokee has enough to provide for all, no matter how large the appetite. That is unless we take more than we need. The people that lived here for thousands of years managed to cooperate with their environment, never threatening their neighboring species and their way of life. I hope that we can also find a balance between taking and giving, modifying our habitat and letting it be. Or else there may not be a place like this for our successors to see — or hear.

If you like this post, you might also enjoy this one where I describe the Colombian scientists’ effort to eradicate coca plants using a special kind of moth. Click below to read:

Why Are Nocturnal Butterflies Addicted to Coca?

Coca plants have been grown and used in the Andean regions of South America for at least 8,000 years. But the "cocaine wars" have made it a target for dangerous pesticide fumigation campaigns that threaten to destroy the native ecosystems. Who is to blame? And how do we fix this problem?

Great story, thank you for sharing.

I’m an ecologist too, so this is playing devil’s advocate: what about the biting insects? Both in your narrative and as a possible reason for humans not getting on well with nature?

Beautiful!!!!