The Mother of Soviet Penicillin

Research collaborations and scientific espionage in the Cold War antibiotics race

When I was growing up in the 1990s in Belarus, the biggest spring holiday was not the floating Easter Sunday but a fixed date—March 8th.

International Women’s Day was a big deal, bigger than Christmas. Although the spirit of this political holiday had morphed over the years reflecting the changing nature of feminism—from its original intention to commemorate women’s suffrage to one that is closer aligned with Valentine’s Day spirit—it remained a national holiday in post-Soviet countries even after the fall of the USSR.

The Soviet regime had designated International Women’s Day as one of its official holidays. For anyone who is surprised by that fact, here is a little bit of historical context. After the Bolsheviks’ Revolution of 1917, the communist party, which advocated equality for all, established legal parity between women and men. This progressive move encouraged the participation of women in the labor force and emancipated them from domestic duties, thanks, in large part, to free childcare1.

Thanks to the increased participation of women in all spheres of life, the 20th century saw countless outstanding achievements by women in leadership, sports, science and other realms. One of the prominent Soviet scientists was a microbiologist Zinaida Yermolyeva, known in the West as Madame Penicillin.

In 1921, at the age of 23, Yermolyeva graduated with a medical degree. In 1925, she was already the head of the Department of Microbial Biochemistry at the USSR Academy of Sciences, where she did research on bacteriophages and naturally occurring antimicrobial agents. But her lasting fame came later, after the Second World War.

During the Second World War, when men were sent off to the front to fight the Nazi army, women became the majority of the manufacturing workforce. (Side note: women also participated in combat. Over 800,000 women enlisted in the Soviet Army, making up close to 8% of the combat force by the end of the war). Behind the defense line, women worked at aircraft plants, headed ammunition factories, operated heavy machinery, performed surgeries and conducted scientific research.

Yermolyeva's expertise in microbiology research suddenly gained a lot more importance with wounded soldiers dying from infections in the hospitals and deadly epidemics of diseases like cholera at the front. Arguably, one of the most powerful biotechnology weapons in the ongoing war was penicillin, which was developed by British and American Scientists in the early 1940s. Yermolyeva, who had been conducting research on bacteriophages and other anti-bacterial agents, was tasked by the Soviet government with producing “homegrown” penicillin.

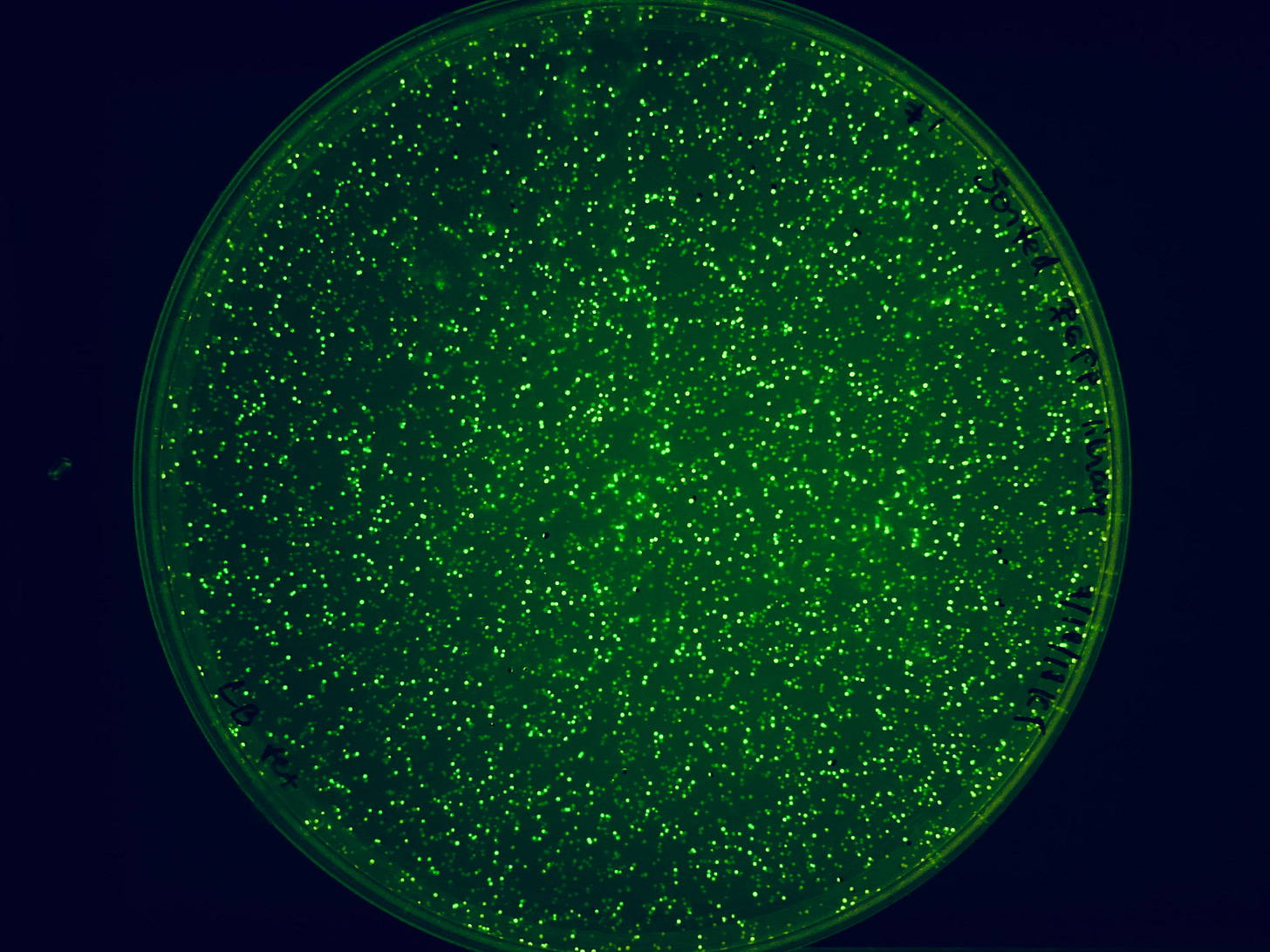

Having read the research on the isolation and characterization of penicillin in the 1941 Lancet paper by Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, Yermolyeva asked for samples of strains from the researchers at Oxford University. But because of competing government and business interests, she did not receive them. So, in 1942, Yermolyeva, with the help of her lab assistant Tamara Balezina who literally collected a hundred samples of mold to try to find one that produced the antibiotic, isolated the powerful drug from the fungus Penicillium crustosum.

By 1944, “penicillin-crustosin” (named after the fungus that produced it, according to the scientific convention) or alternatively “penicillin V.I.E.M.” (after the Institute of Experimental Medicine where it was made) was being used in Soviet hospitals. It was one of those wartime miracles, a tour-de-force achievement that accomplished something that normally takes decades in less than two years.

The same year, Florey visited the Soviet Union and exchanged samples of penicillin with Yermolyeva, who in turn gave him a sample of the antibiotic Gramicidin. During his two-month-long stay, Florey went to the Bolshoi theater six times and collaborated with Yermolyeva to compare the Soviet2 strain to Fleming’s original Penicillium notatum. A common goal—the fight against the Nazis and bacterial infections, both killing millions of people—spurred this scientific collaboration, unimpeded by physical or ideological borders.

A case of scientific espionage

But the story of Soviet penicillin doesn’t end here. Yermolyeva’s discovery of penicillin from mold would have been useless without the ability to produce it in commercial quantities. One of the biggest challenges of biotechnology is figuring out how to scale the production of a useful biological molecule like penicillin. That includes identifying high-producing strains, developing a robust fermentation process, purification protocols and stable formulations for the use in clinic.

Although Alexander Fleming received most of the credit for the discovery of penicillin, it was Florey and Chain who took note of this discovery and made it into a useful drug. They worked with American scientists to develop a commercial process for penicillin production, which included isolating a high-producing penicillin strain from a moldy cantaloupe and scaling up its production in industrial fermenters.

So, by the end of the war, the USA was producing a thousand times greater quantities of penicillin than the USSR, and the Soviets had to buy the antibiotic from abroad to meet the demand. The Soviet government had a strong financial (and ideological) incentive to develop their own production process. At that time, they had outdated technology and an inefficient process based on surface fermentation and low-yielding strains. Luckily, Florey’s visit established a relationship that opened a door for scientific exchange.

So, in 1945, a little-known person by the name of Mr. Borodin led a Soviet delegation of scientists on a research trip to London. Due to political and business reasons, the penicillin technology was vigilantly protected by the interested parties that did not want to share the patented penicillin strains. But Borodin managed to form a close relationship with Florey’s colleague Ernst Chain, whose personal leanings made him sympathetic to the Soviet colleagues. A few months later, the coveted strains traveled back to the USSR in the pocket of one of the delegates, along with intel on the novel fermentation technologies. According to recently de-classified documents, this played a pivotal role in establishing industrial penicillin production in the Soviet Union.

A biochemical propaganda tool

The origin of the technological advances that enabled Soviet penicillin production was conveniently omitted. After the war, the antibiotic drug became known and marketed as “Soviet penicillin”. It became a powerful propaganda tool to demonstrate the strength of Soviet science and progress in medicine and domestic manufacturing. Yermolyeva was bestowed the highest civilian decoration, the Orden of Lenin, for her research on penicillin and promoted as the founder of the antibiotics industry in the USSR.

In my opinion, that is a bit of a twisting of the facts. I don’t say that to diminish Yermolyeva’s contributions to science. She always appropriately credited the strains to their respective owners; it was the bureaucratic paper-pushers that scratched out the scientific facts and replaced them with propaganda-friendly names. Perhaps if scientists were able to exchange their research findings freely, without ideological constraints, Yermolyeva would have established the domestic antibiotics industry without scientific espionage.

Her contribution to Soviet science was remarkable, nonetheless. Of the most lasting consequence was perhaps her importance as a role model. By a twist of fate, Yermolieva’s husband’s brother was a novelist who used her as the protagonist in one of his books about a female scientist. Over the following decades, this popular book inspired many Soviet girls to consider a career as a microbiologist. And the legacy of biological sciences remains strong in post-Soviet countries to this day.

The revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin stated: "Petty housework crushes, strangles, stultifies and degrades [the woman], chains her to the kitchen and to the nursery, and wastes her labor on barbarously unproductive, petty, nerve-racking, stultifying and crushing drudgery."

The Penicillium crustosum strain produced higher amounts of penicillin than Penicillium notatum.

Real interesting history!