I’ve been writing a lot lately about how biology—whether in the form of invasive species or jumping genes—can reshape our environment. Similar to living things, our beliefs also shape the world around us. And the same way we should take care to not let biological organisms propagate uncontrollably, we should be cautious about what ideas we seed out there and how we contribute to their spread. As Richard Dawkins pointed out in his famous book The Selfish Gene, memes, just like genes, can propagate, mutate, compete, and generally take on a life of their own. So, let’s talk about perhaps the most powerful way of spreading ideas—through art.

During the Dark Ages, religious worldviews dominated the collective consciousness. The worth of an individual was dictated by the church, which basically said: “You are worthless”. Humans were viewed as fundamentally flawed—in contrast to God. That is, until Petrarch and Bruni, alongside other Italian thinkers, re-discovered the writings of Ancient Greeks and Romans, and began developing a new body of secular literature, resurrecting the ideas of antiquity which granted a lot more agency, creative expression, and moral autonomy to man. Needless to say, the church did not like those Florentine heretics.

The city of Florence had had some beef with the church for a while. The city-state rivaled the papacy in the 13-15th centuries in terms of its economic and political power. I imagine it is not by chance that these heretical humanist ideas were allowed to bloom in Florence. During the Renaissance, man’s god-like status, which he lost with the decline of the Roman empire, was reinstated. Humanists believed in the goodness of man and the harmony of the universe. They advocated civic responsibility, active participation in political and social life, and upholding exemplary moral standards. These ideas soon spread to Europe and pulled it out of the Dark Ages.

But the way it happened was not through scientific discovery or legislative reform. The driving force behind disseminating the ideas of the Renaissance was art: Petrarch’s poetry, Ghiberti’s sculpture, and Michelangelo’s frescoes. Art served as a vehicle to deliver those revolutionary ideas via a powerful symbolic form.

Most people associate Renaissance art with Michelangelo’s statue of David or Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. However, one of the original minds that poisoned the well of the Florentine intellectual elite was actually Brunelleschi. He is the architect responsible for creating Florence’s most recognizable landmark—the Duomo. But before Brunelleschi created his masterpiece, he spent 10 years studying the ruins of Rome and the ancient treatises on architecture.

That self-guided education led him to rediscovering the ideals of beauty of classical antiquity, which aligned with the philosophical leanings of the humanists. Brunelleschi conveyed the intellectual and civic values of the time through art. Others, such as Donatello, Ghiberti, Michelangelo, Da Vinci, and Botticelli, followed in his footsteps and created masterpieces that still instill a sense of awe in us. These artists saw and depicted beauty, harmony, and intelligent design in everything from the human body to architectural forms. And this powerful visual representation helped deliver humanist ideas directly to people’s subconscious minds.

It was art—not philosophical discourse, didactic teachings, or other forms of rationalization—that defined the Renaissance. You can rationalize anything, using (sometimes faulty) logic to arrive at a conclusion you are trying to prove. But the rational mind is not nearly as powerful as our feelings. To change paradigms, you need to move people. To make them feel something so strongly that their life splits into before and after. To penetrate so deeply into their psyche that they cannot unsee, unhear or un-understand the truths that have been imparted onto them.

This is what art does.

Art propaganda

Art is one of the most powerful propaganda tools out there. Take Hollywood, for example. It is hard to argue that Hollywood has spread American values and way of life to the rest of the world. People in far corners of the world give up their unique, authentic cultures in favor of the Westen lifestyle. The standards of beauty have become dangerously homogenous thanks to Hollywood. The glamorization and heroization of war have led to a careless disregard for the real consequences of violent conflict (take, for instance, Oppenheimer, that failed to show a single Japanese casualty of the atomic bomb).

Film was also Stalin’s favorite propaganda medium. The ideas of communism were reinforced by monumental sculpture, large-scale murals—done in the emblematic style of Soviet realism—poetry, literature, and, of course, cinema. Perhaps the best example is Battleship Potemkin which describes a revolutionary uprising of 1905 and is widely considered one of the greatest films of all time. Without this cultural tour-de-force, it would have been hard to maintain optimism in the bright future of communism during the horrid civil war, famine, executions, and political repressions of the 1920s-1930s.

Art is a powerful vehicle for spreading ideas like wildfire, and it can be used for good or evil. A sure way to understand where our society is headed is to take a look at the art that is captivating our minds today. What do you see? Or, perhaps, more importantly, what do you CHOOSE to see?

My advice is: Be careful what you expose yourself to. Ideas, just like viruses, have a tendency to hijack you and take root inside you. But unlike a virus, they can be much harder to get rid of. Even seemingly benign things will leave an imprint on your subconsciousness. So, think about it: do you want the Kardashians, with their artificial beauty, to live there rent-free? Do you want the images of pointless violence to slowly desensitize your brain to it? Do you want to develop tunnel vision from only listening to one-sided conversations?

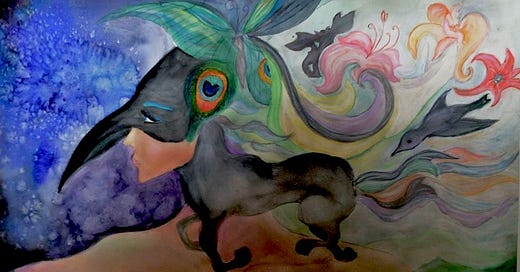

Of course, we cannot simply close our eyes and ears to what is happening out there, to ignore popular discourse, even if it is unsavory. But at least we can stop the spread of those virulent ideas—the memes that only reflect a part of the complexity of the issues they try to pack in, a black-and-white version of reality. Instead, let’s keep seeking and spreading the beauty, harmony, and multicolored nuances of life.

If you are interested in learning more about Brunelleschi’s role in resurrecting the style of classical antiquity and his legacy on modern architecture, check out this article I wrote:

https://www.lifeofascientist.com/legacy-of-classical-architecture