The Mayan Calendar and the End of the Western Civilization

Another year has come and gone, and the world still has not ended. Ever since 2000, we’ve been living in anticipation of the apocalypse – of technological or natural origin – and every year it seems more and more likely. Yet, we are still here, about to welcome in 2023. First of all, congratulations on adding another year’s worth of contributions to your 401(K) in the hopes of using it one day. Jokes aside, we should feel pretty grateful and lucky for being here at this moment in history. We have conquered most known infectious diseases and the emerging antibiotic-resistant ones have not taken over yet. We have electricity and running water on demand, the ability to circle the globe in less than a day, and access to hundreds of years’ worth of information at our fingertips. Looking back at this time, future historians will probably call it the height of Western civilization.

But being at the peak means that the next phase – the decline – is inevitable. No civilization in the history of humanity managed to survive for more than a few centuries without experiencing dramatic fluctuations. In biology, we see the same natural law governing population dynamics in most organisms, even primitive ones like bacteria. In the beginning, a small number of microbes experience slow and precarious growth. Their priority is survival, and they only utilize resources for essential functions like basic metabolism and reproduction. Once that population reaches a critical mass, it starts increasing exponentially. What typically happens during this stage can only be described as a big party – resources are abundant, the population is stable, and the atmosphere is euphoric. A microbial colony starts producing complex chemical molecules that are not essential for survival – almost like works of art or cool gadgets we humans make. But then one day, the resources become scarce, and waste products of life start accumulating in the environment and poisoning cells, resulting in a sudden and massive population drop.

Our current civilization (which we refer to as the “Western civilization”, although it has no roots in the cultures of the Western hemisphere) is likely going to experience the same fate. And we all know it, whether on a conscious or subconscious level. There is an obsession with catastrophic narratives in news, documentaries, and films, spanning scenarios from asteroid collision to a nuclear blowout. These stories seem to hold an exceptionally strong grip on our imagination, which tells you something about the times we live in. When the anticipated end of the world according to the Mayan calendar did not happen in 2012, our society was left with an internalized sense of anxiety. Of course, the Maya did not predict that the time horizon would stop in 2012. It was simply the end of the Long Count calendar cycle, which was back-calculated to align with a unique winter solstice on December 21, 2012. On that date, the high noon position of the Sun projected exactly over the galactic center, an event that occurs only once every 25,772 years.

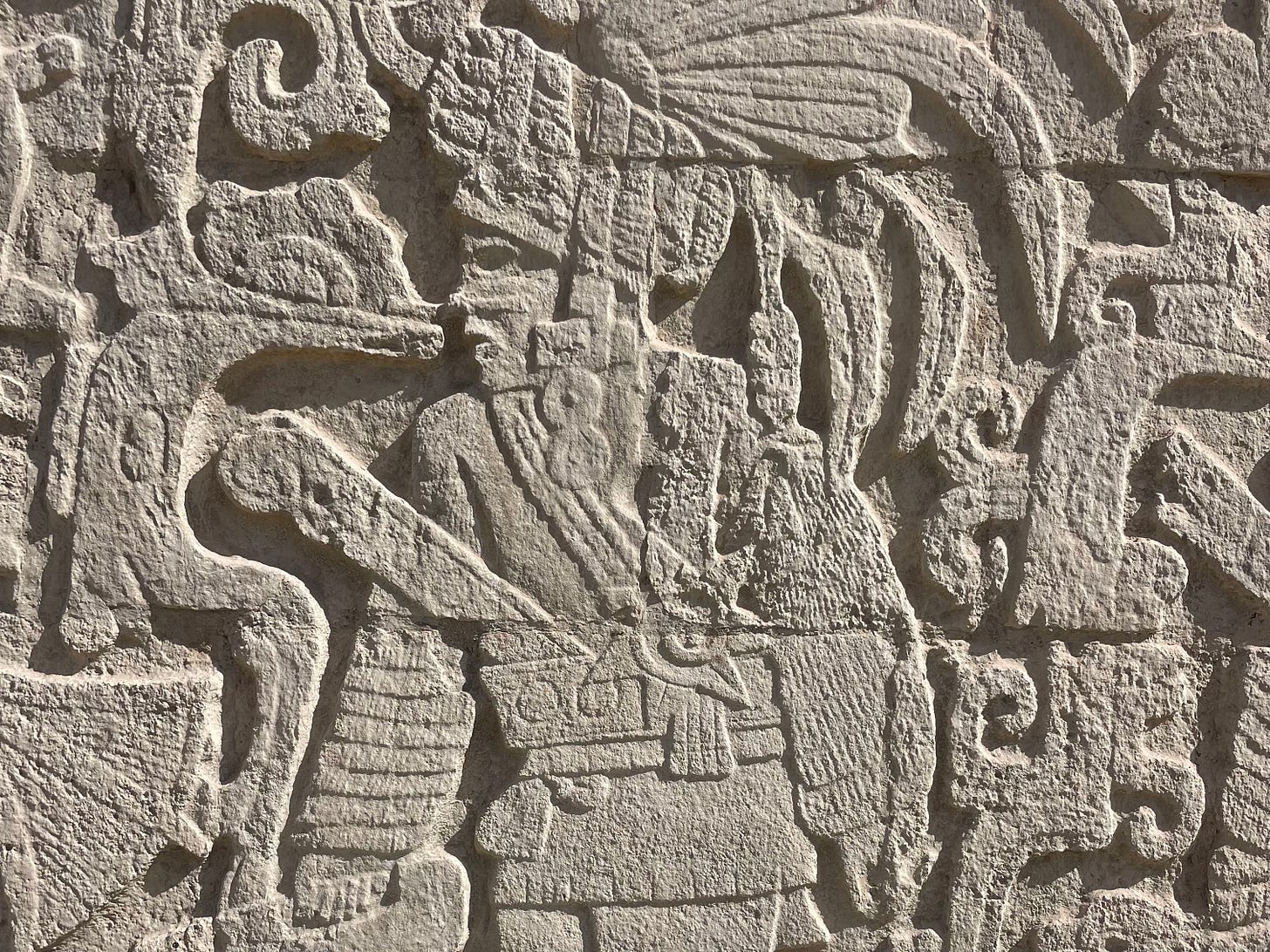

The precision with which the ancient Mayan civilization was able to calculate the alignment of the Sun with the center of the Milky Way Galaxy is uncanny. This feat of human ingenuity (its effect amplified by the fact that we massively underestimate the cultures that inhabited the Americas before the arrival of European invaders) produced mass hysteria thousands of years later, when hordes of New-Age believers gathered at Chichen Itza on December 21, 2021, to celebrate the end-of-days with regional burn party. They were by no means the first to do so – Chichen Itza has long been a center of ceremonial gatherings meant to stave off the potential apocalypse. Fear of death is a very effective way to control people, and Mayan priests knew well how to make an impact on the populace. Located in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, Chichen Itza was a center of politics, trade, culture, and religion for the Maya people. The city’s famous pyramidal Temple of Kukulkan, which was built around 1000 AD, is a physical representation of the Mayan calendar. The pyramid stands an imposing 98 feet tall and is aligned with the movements of the sun, marking the points of the equinoxes and solstices. Each side of the pyramid features 91 steps, with the final platform at the top adding up to 365 steps for each day of the solar year. The orientation of the temple is such that on each equinox, the sun casts a shadow on the steps of the pyramid, creating an illusion of a snake creeping slowly down the northern staircase. Another less prominent but no less important building stands not far away from the ceremonial pyramid – a secular Observatory, which was used for mapping out the precise movements of stars and galaxies, so as to be able to predict their positions thousands of years ahead.

By the time the Mayan people built the massive city of Chichen Itza in the heart of Yucatan, the civilization had already acquired centuries of knowledge: knowledge about their natural environment, properties of materials, precise observations of the movement of the stars, and even the speed of sound. Knowing the speed of sound allowed the Mayan architects to create some really cool acoustic effects at the temple of Kukulkan: clapping in front of the pyramid generates a sound that mimics precisely the call of the quetzal bird which was revered by Maya. This colorful species is indigenous to Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Central America’s highland regions. When Mayas migrated from Guatemala to Yukatan, they could not bring the bird (it simply did not live in the new climate) but they eternalized the sound of it in the echo effects at the temple of Kukulkan. Archeologists believe that the bird is the protagonist for the snake god Quetzalcoatl, a feathered serpent that descends from heaven on the day of the solstice. This myth is played out in motion when the sun hits the pyramid at the exact angle to create an illusion of the serpent god descending down to Earth.

The archeological site is impressive not only from a cultural but also engineering perspective, and it reminds us of the forgone glory of the Mayan civilization. It is a common misconception that the Maya disappeared, with many speculative theories about what natural or supernatural disaster could have caused it. Although the population has seen a significant decline since the height of the empire, the Maya have not disappeared but rather assimilated among other modern inhabitants of Mexico. They still carry the language, customs, and distinct phenotypic features that define this ethnic group. But much of the religious and cultural beliefs have been forgotten, and most of the written records from this incredibly advanced civilization have been destroyed. By the time the Spanish conquistadors arrived at Chichen Itza in the 16th century, the city had been largely abandoned, following a gradual decline of the empire over the previous five centuries. Unfortunately, the reason for the decline is a lot more prosaic than the legends of the wrath of gods or the clash of empires that we may imagine. Ancient Chichen Itza had an estimated population of 60,000 people, and the city simply overused the resources of the surrounding area. There were no more animals left to hunt. The fertile jungle soil became depleted of minerals and nutrients and the crop yields dropped. The land simply could not support the population anymore.

Does the same fate await us? Will our culture be lost just like Mayan? The majority of the remaining written records that detail their knowledge of astronomy and tell us about how the ancient Mayans lived are the ones carved in stone – one of the most durable physical materials that can survive most cataclysms. Today, we are less concerned with durability and more about building our legacy in the cloud. But what if an EMP destroys the internet? Or a massive die-off happens? A global catastrophe that wipes out a large percentage of the population – not unlike what happened to the Maya – could set humanity back hundreds of years. In today’s world, people’s skill sets are becoming increasingly narrow, where one person may know how to code but not how to build a circuit. All our digital heritage may be forever lost in the ethers. Will future civilizations think we were primitive based on how little information remains of us? Will they also marvel at the tall buildings we left behind and think that it must have been aliens that taught us how to build things if they cannot find any architectural drawings to back up human authorship?

Civilizations are incredibly fragile, and while at the height of our glory it is hard to imagine that anything as advanced as our society may disappear someday, that is most likely what will happen. The question is – when? It could be in a million years or it could tomorrow. There are subtle shifts in our environment and in our lives happening every day but we tend not to notice them. While we distract ourselves with pseudo-archeological docuseries about the mysterious disappearance of ancient civilizations, our own apocalypse may already be underway.